The Warsaw Jewish Cemetery is the largest Jewish necropolis in the capital city of Poland, the second largest Jewish cemetery in Poland, and one of the largest Jewish cemeteries in the world. It was established in 1806, and the oldest grave markers preserved on the site date back to the first decade of the 19thcentury. It is the final resting place of many outstanding members of the Jewish community: clergymen, scientists, industrialists, writers, soldiers, and social activists. This is where the graves of Ludwik Zamenhof, the inventor of Esperanto, or of Marek Edelman, a leader of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, can be found.

The cemetery spans over a surface area of approx. 33.3 ha and boasts around 200 thousand grave markers – offering one of the most valuable collections of sepulchral art not only in Warsaw but also in the entire Poland. Most of the grave markers, measuring from several dozen centimetres to even 2 metres in height, are made of richly decorated materials, e.g. granite, multi-colour sandstone, and regular stone. Memorial tops have usually the form of a triangle or a semicircle. The reformed part of the cemetery features a range of monumental graves, sarcophagi, and richly-styled mausoleums.

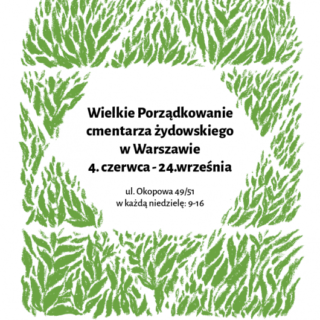

The necropolis, remaining under the care of the Jewish Community in Warsaw since 2001, miraculously survived the time of WWII. In the post-war period it was left neglected for many years, gradually falling into ruin. But with time there occurred occasional attempts to restore it to its former glory. The Cultural Heritage Foundation is now running conservation and clean-up works at the same time. The latter have an additional social impact as they often bring together volunteers and supporters of our foundation. The undertaken activities include mostly collecting and removing trash, broken branches, and self-sown plants from the cemetery quarters.